Life is hard for active managers in certain developed markets.

Some 67 per cent of actively managed US equity funds failed to outperform the S&P 500 in 2017.

For the decade to the end of that year, this number rises to a whopping 93 per cent, S&P Global research finds.

The US market is notoriously difficult for active funds because it is highly efficient: information spreads quickly, and new developments rapidly move prices.

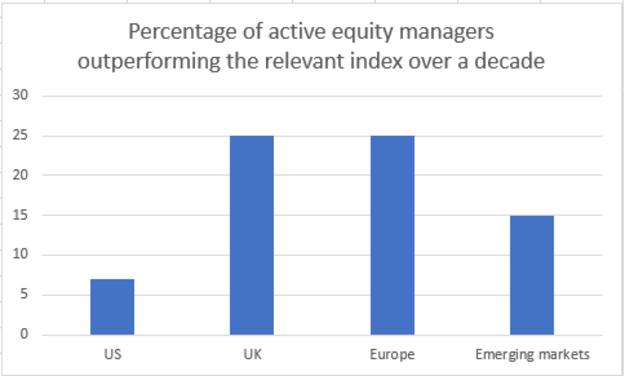

But as Figure 1 shows, active managers have fared better elsewhere, even if their success rate is far from overwhelming.

Figure 1

Source: S&P Global

In the case of frontier markets, not specifically covered by the data, passives are available for the grouping as well as individual countries, but several arguments can be made for going active.

Firstly, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), a popular form of passive vehicle that can be used to quickly enact trades, are unlikely to function well here because of a lack of liquidity.

Secondly, the countries grouped together by indices can be a disparate bunch, in a region where picking the right investments is vital.

Another argument is that a lack of information about many of these markets, due to a lack of transparency, or the fact not many analysts will cover these areas, presents an opportunity for active managers who can do their research and invest accordingly.

Active allocation

For those choosing an active fund, there are three main possibilities, each with its own pros and cons.

Investors with passion for an individual frontier market can look at those single-country funds that are available. This can help give a portfolio greater exposure to what may turn out to be a success story out of the group.

Finding such funds may require some digging, given their specialist nature, but a handful do exist. At least three funds, from providers such as VinaCapital, focus on Vietnam, for example.

Individual markets can perform particularly well at times.

But Ryan Hughes, head of active portfolios for AJ Bell, suggests that the immaturity of frontier markets remains a big barrier to picking an individual country.

“At present, all of the frontier market countries should be considered as too immature to be considered as investments in their own right,” he says.

“Questions of the depth of market and liquidity make it difficult to justify a specific single-country exposure at this stage.”

Another option is to buy a dedicated frontier markets fund, which offers a more diversified level of exposure to this group.

Some open-ended offerings include T Rowe Price Frontier Markets Equity, which is run on an unconstrained basis (see Figure 2 for breakdown) but focuses on quality to potentially reduce some of the risk involved. Barings and Franklin Templeton also offer products here.

Another fund, Fiera Capital’s Magna New Frontiers, has performed well but closed to new investors as it approached capacity constraints last year.