Bond yields in developed markets remain extremely low and look unlikely to rise by much in the near term.

This, understandably, has pushed investors into riskier but higher-yielding assets, from infrastructure to emerging market debt.

What role do frontier markets play here?

As with equities, frontier market bonds tend to look more attractive than their emerging market peers, because they can be cheaper and offer higher potential returns. Equally, they bring bigger risks.

However, emerging market debt has endured a difficult 2018.

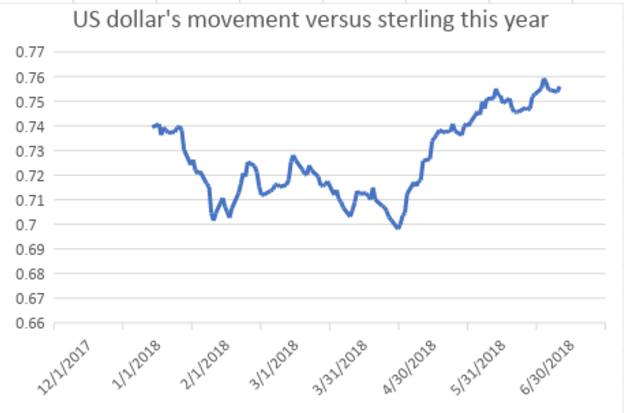

Pieter Jansen, senior multi-asset strategist for NN Investment Partners, notes that a strengthening US dollar (highlighted in Figure 1), higher commodity prices, macro uncertainty and country-specific concerns triggered a sell-off.

Figure 1

Source: FE Analytics

He believes frontier market bonds look like a good alternative.

“We favour frontier market debt, which offers higher yields together with short durations compared with emerging market debt generally,” he explains.

“Frontier market economies are likely to grow at a higher rate than developed and emerging economies. Given improving fundamentals and attractive valuations, we continue to expect positive returns from this asset class for the medium and long term.”

Fixed income markets in these countries tend to be very inefficient, with issues such as illiquidity and an absence of information likely to put some off.

But this can also create opportunities.

Opportunity knocks

“Frontier markets are not as well researched as other markets,” explains Stephen Penfold, senior investment manager for wealth firm 7IM.

“Information on both countries and companies is less abundant than it is in [for example] the US or UK markets, and companies and management are less likely to be subject to the same level of scrutiny and regulation as their developed market counterparties.”

But this, he adds, can create more trading opportunities for those that can do the necessary research.

There are tentative signs that such markets could function better in future, even if this means more competition for investors currently operating in the space.

Mr Penfold notes that frontier markets have outperformed other areas in the fixed income space. If these returns draw in more investors, the influx could prompt an improvement in standards.

Other developments could also bring longer-term benefits for investors.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been much more active in lending financial support to sub-Saharan African countries in recent years. Nine of the 21 countries in the region rated by Fitch were in active programmes, up from just three in 2014, according to the credit rating agency.

The increase in IMF activity demonstrates the difficulties these countries have faced in recent years.

But according to Aaron Grehan, an emerging market debt fund manager for Aviva Investors, it also signals a growing willingness among African governments “to implement the kind of painful yet beneficial macroeconomic adjustments the IMF recommends”.

Some of these nations now offer attractive debt. Ghana issued $2bn of government bonds earlier this year, adding to a series of fixed income products across different levels of maturity, including one that paid a 10.75 per cent yield and came with World Bank backing.